How I Write (Now)

by Brad Ricca

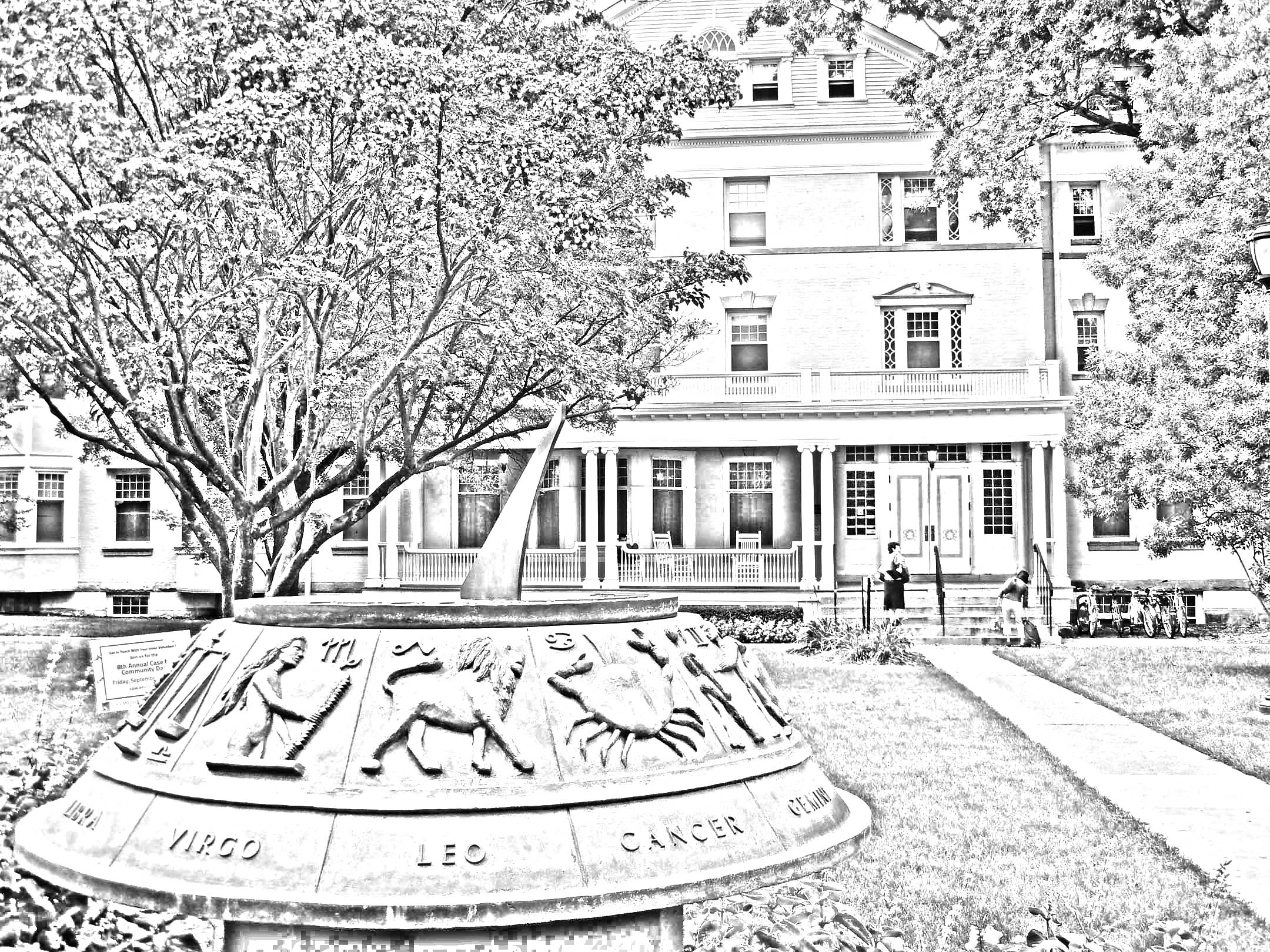

This past fall, I was asked by Professor Vinter to give a talk on writing nonfiction. I was flattered to be asked to come back to Guilford – back home – to be with people who wanted to talk about things other than Spongebob Squarepants. I was even more excited when she suggested we make it about process. I try not to be a big advice person, so I approached it as things I wish I had known when I started. Here’s what I think I’ve learned.First, writing for a trade publication (an article in a magazine or a book in a store) is not that different from writing for an academic one. Though the styles may differ, the process depends on the same intellectual and written kung fu that any English major, MA, or PhD student knows better than anyone. It just happens in reverse. An English major writes a paper on Frankenstein by looking at the creature and analyzing it from a variety of critical approaches. They take the monster apart to find meaning. But the nonfiction writer gets to take the opposite approach. We get to make the monster.But how? I hear you asking. First, I choose what I call a secret theme. What do I really want to write about? Think about? Learn about? And admittedly, get others to engage with? These themes lurk in the shadows of everything I do and are broad and unwieldy topics: creativity (Super Boys), missing girls (Mrs. Sherlock Holmes), whiteness and suicide (Olive the Lionheart), and conspiracy thinking (True Raiders), but they are never the story itself. I will explain why in a moment. Once I’ve got my secret theme, I go hunting for a specific story to, for lack of a better term, get into it with. My own process isn’t efficient: I cast a wide net by looking in archives, newspapers, and so on. This can be the worst part sometimes, but it’s also the most exciting. Looking for a story – one that fits me and what I want to write about – is a weird combination of time travel and luck. It is frustrating, but when you finally find something, when you find it (and can get by those next several minutes of intense Googling to make sure there aren’t twelve books on the subject), well, that is the good stuff.

Story is important. It should be, by all accounts, entrancing! thrilling! topical! Most editors prefer that it also involves murder, the Civil War, or Nazis (in that order), but you can ignore that. It just has to be good. But what is a good story? And how do you tell it? Hey Brad, I don’t have an MFA from Syracuse! And I hear you again. But come on. You know this already. You know all the elements of good literature that you can name, analyze, and lecture on (with all due respect) until the first three rows of any classroom in America are asleep. You know how your favorite works of literature work. I’m not saying it’s not magic when a good book works, but I’m saying you know the magic. Model the works you like, ape them, transform them. A good story has good content (which all your specific areas of expertise have), but it is also how it is told. I almost gave up on my last book because I had a bunch of different narrators (some of them highly unreliable) and I couldn’t figure out how to organize it – until I remembered As I Lay Dying (thank you Williams – Faulkner and Marling). Storytelling is a skill of techniques. Creativity doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Writers are readers. Cliches are endless.

Still, I hear you again: how do I write the actual sentences, man? I would suggest organizing your writing into scenes. Instead of paragraphs about Charles Dickens and his writing process, study old accounts, photographs, and weather reports to bring that place to life. You don’t want your readers to see flat words standing in for meanings in a dictionary. You want your words to smell, taste, and feel like something. You want your readers to be there.

Why? Because your reader wants to be there. After all, they bought the book! To get the reader of an academic piece to stay interested, you offer more evidence to carry them along your line of thinking. In a trade work, you do the same, but through suspense. Reveal things bit by bit. The act of holding the shark or xenomorph – the subject itself – in the background will help create a sense of story through suspense. But what if I’m not writing about scary aliens? The experience we love of researching, reading, and thinking is also a kind of suspense – as discovery – that your reader wants to experience with you. The books I like that do this – In Cold Blood, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, The Legend of Colton H. Bryant – are problematic texts in many ways, but they offer up significant spaces of discovery for the reader. This is why I write about real stories and not their secret themes. For one, writing about the theme itself would be boring; a theme is something Charlie Brown would get a D+ on. By instead creating a space between the story and the subject – as a metaphor – the reader has yet another space to engage in. If the reader can make meaning there – or find horror of a different kind – then the work (I think) becomes deeper and hopefully more persuasive; it becomes a better story. Tell the truth, but tell it slant (thank you Emily D. and Gary Stonum).

When I first started this type of work, I obnoxiously thought “Oh, I just have to take my academic writing and ‘dumb it down’ for a ‘general audience.’” I wish someone would have punched me (though gently). I was very wrong, and quickly learned so. The only thing you can safely say about a trade audience is that it is BIG. It is the largest, most diverse classroom you can imagine. That, to me, is terrific. And they are reading for the best reason of all: they want to. It is so much harder – and satisfying, for me – to write for an audience like that because it’s not about changing any big ideas, just thinking more about how best to employ them.

I’m not trying to make you question your path or interest you in an alternative lifestyle. No, a nonfiction trade book will not get you a tenure-track job in the 18th. C., but it could get you a job in a writing program. Freelance writing will never get you health insurance (thank you, Caroline), but the pay can be good, and it can get you noticed, if that’s something you want. There is no peer review, but there are plenty of editors, copy editors, lawyers, and eagle-eyed critics on Goodreads. You can also use a lot more em dashes. All I’m saying, I think, is that I’ve found this type of writing to be another kind of market for the skills I was trained in, which are, thank God, the things I love to do. It is hard work, and sometimes uncertain, but I’m able to chart my own path. I’m not saying it’s the best path or the worst, only that it exists.

If you have questions, want to see a template book proposal, or want to brainstorm an idea, I am happy to help. For though the story of this little essay was how I write now, the secret theme was simpler: If you can analyze a story, you can tell a story. And you have a major head start.

Brad Ricca earned his PhD in English from CWRU in 2002 and taught there for nearly twenty years as a full-time lecturer. He is the Edgar-nominated writer of five books, including his latest True Raiders (St. Martin’s, 2021). See more at brad-ricca.com. |