This newsletter has been edited in order to remove some regrettable language in the original version and to ensure that the English department remains an inclusive place for all.

From the Department: Thank You

The English Department could not have been more fortunate in the selection of Professor Georgia Cowart to serve as our Interim Chair over the last two very challenging years. Chairing a department successfully is hard enough without having to do so on a temporary basis, coming from an external department, and beginning the job in the middle of a global pandemic. To navigate this situation with grace, humanity, and humor, conveyed mostly over the stilted medium of Zoom, was a feat of administrative magic.

When she agreed to this leadership role, Georgia, a Professor of Music specializing in Early Modern French arts and cultural politics, already had more than enough experience for the task, having joined CWRU’s Music Department as its new chair in 2002, shepherding it in that position until 2007 and then later serving as its Coordinator of Graduate Studies in Musicology from 2014-2020. Shortly after that, in an act of both kindness and optimism, she agreed to help us out in the English Department. As she steps down at the end of June, and prepares to step up as President of the American Musicological Society for a two-year term beginning in November 2022, we are deeply grateful for her sure-handed guidance, her tact, and her geniality amid turbulence and change.

I recall wondering whether Georgia was aware of the particular complexities facing the department when we first met about the transition in March, 2020, three months before I stepped down as chair. Georgia would have to staff courses and committees with the department at a 20-year low in faculty appointments. She would need to seek urgent tenure-track lines amid a hiring freeze, and to mentor and evaluate faculty in a discipline other than her own. She would be required to align the various moving pieces in the department’s relationship to SAGES, the College of Arts and Sciences, and the University. The job would be daunting at the best of times, but her two-year appointment also coincided with significant administrative shifts at CWRU, including a new dean, a new president, and a recently appointed provost. There was, in other words, little pre-existing knowledge, informed direction, or sense of continuity that the College or University could provide. And then, just before she started, the pandemic arrived, both amplifying existing stresses and adding new and unforeseen ones. Looking back, I realize that I should not have worried in the least. Right from the beginning, Georgia met all of these challenges with the equanimity that the English faculty have come to see as her abiding strength.

Georgia’s commitment to what she calls “radical hospitality” meant that she immediately treated her new department colleagues as valued individuals, promoting their work as scholars, teachers, and administrators, and working diligently to get to know what mattered most to each of them. They responded with unified energy. Asked about Georgia’s impact on the department, Mary Grimm, another former chair, first noted “how kind Georgia is, and how well she managed our unruly department without ever raising her (rather lovely) voice,” before marveling at “how astounding it was that she liked being chair!”

Other faculty members have praised her dependability, fair-mindedness, and calming influence. “Her quiet diplomacy and her manner of speaking slowly and carefully,” Kim Emmons said, “helped steer the department through two difficult years. She brings an air of genuine curiosity to every conversation and reserves judgment until she has heard all sides. She has been an important role model and mentor to me, personally, and to the department in general. (In my experience, that has meant an apparently inexhaustible patience for email, a willingness to meet often and at length, and a genuinely people-centered ethic of leadership and care.)” As Rob Spadoni observes, “she stepped into the leadership vacuum of a shrinking department and supported faculty research efforts, including coming up with creative ways to do so when the available funding and resources were limited. I also appreciated the cordiality and considerateness she brought to the tone of department communications and meetings.” Michael Clune adds that she “managed to bring together different department factions and to make everyone feel as if their voices were being heard.” He also notes that “her combination of graciousness, committed advocacy, and diplomatic skill proved crucial in achieving a successful search for a new chair.”

Repeatedly, faculty comments emphasize the extraordinary conditions Georgia faced. Reflecting on the unique challenge of chairing during a pandemic, Thrity Umrigar recollected the concern she felt about the impact of social distancing: “I felt terrible that she seldom got to see most of us in person and unmasked until the last few months. But it now occurs to me that Georgia was exactly the chair we needed to shepherd us through these unprecedented and tumultuous times. We needed her deep compassion, her gentleness, her kindness, and her warmth during a time when we all felt a little adrift and disoriented. I appreciated how often she’d start department meetings by asking us how we were doing and urging us to do a bit of reflection about our emotional states.”

I am confident that Mary Grimm speaks for us all when she applauds the way Georgia confronted “the increasingly difficult administrative tasks of the pandemic year, serenely undaunted, and tirelessly advocated for the department’s needs with the administration. We were so lucky that she agreed to chair English.”

Thank you, Georgia!

A Tribute to Christopher Flint

by Robert Spadoni

I think it’s okay to say this now that they’re both retiring: Chris Flint and Athena Vrettos are married. They met on Athena’s first day of graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania, where Chris was on the English Department welcoming committee. He asked Athena out the first week of school. Later, living in sin, they worked out a timesharing plan and wrote their dissertations on the same computer, which Athena thinks might have been the very first Macintosh, and which, if you look in the hallway on the second floor, I think you will find along with some French-language VHS tapes.

Upon arriving at Case, shortly after Athena, Chris (or as one of my kids, I forget which, when she was very young, maybe inspired by Boaty McBoatface, named him, Chrissy McFlintball, but I will call him Chris for the remainder of these remarks) quickly established himself as a valuable Department citizen. He was, first, a good teacher, earning rock solid, consistently enviable course evaluations semester after semester. Some of his favorite courses were those of his students as well. There was the seminar in which he set Laurence Sterne’s and Jane Austen’s very different prose styles into a dynamic conversation that structured and animated the whole semester. There was his Print Cultures course, which drew on, and was enriched by, Chris’s deep dive into the topic in his second book, The Appearance of Print in Eighteenth-Century Fiction. He taught a wonderful course on Adaptation, which I heard a lot about from my students, in which Chris assigned canonical works of literature followed by adaptations that tended to be experimental, challenging, revisionist works—not the safest or easiest choices if what you want is for your students to say, “That movie was fun; this class is fun.” These choices were more work for the teacher, and, I think it’s safe to say, more rewarding for his students. This was a course that benefitted, like a great many other things Chris gave to this Department, from one of his real strengths, and this is the eclecticism of his interests and passions, a range that shows a healthy disregard for things like matters of form, century, country, and medium. This wide-ranging knowledge and love flowed, also, into his course on Eighteenth Century Film, where Chris’s little joke was: There are no eighteenth century films; film had not yet been invented. In this course, Chris cast light on what is deeply strange and experimental about Eighteenth Century literature by placing those works alongside film adaptations that are, themselves, strange and experimental.

Ever the good Department citizen, Chris didn’t just teach his little, personal, boutique favorites, but also (and he loved teaching) English Literature to 1800, in which his students were treated to something Chris brought to every course he taught, and this is his highly performative teaching style—delighting students, for example, with his dramatic readings of Satan lying in the lake of fire and cursing heaven. Here is Athena describing Chris’s teaching style: “He wanders around the room a lot and bounces around and does a lot of voices.” In short, Chris got into it, sometimes to the point of his own mental exhaustion, driven on by his inexhaustible perfectionism—and I know about this from our many conversations on the subject. A conscientious and dedicated educator, Chris was constitutionally incapable of phoning it in.

It would be hard to overstate his service contribution to the Department. For his five years as chair, he brought to his leadership of the Department his humanity and fair mindedness—in meetings, for example, where he went out of his way to make sure that people who spoke up less often always knew there was space and encouragement to do so. And he was always looking for ways to better support the lecturers; he was their friend when they faced tough times, which was a lot of the time. He fought to secure new tenure track lines, even when that fight seemed hopeless. He worked with donors, and here his excellent hair and effortless charm came in handy, and it is thanks to Chris that the Department can offer, today, Tim O’Brien Summer Scholarships and Research Funding Support to its English majors.

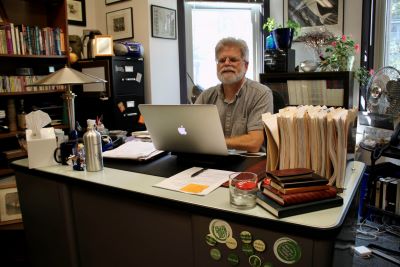

He was always in his office with this door open, and here the tchotchkes crowding every surface performed a devious, strategic function, for one of these curiosities would invariably catch the eye of a student passerby, and they would poke their head in and, within minutes, find themself seated across from a very friendly and welcoming man, with an agenda, and the next thing they knew, Chris would be pushing a major declaration form across his desk, and, often, because this is just the kind of guy he is, a pen.

Chris also directed graduate studies for some years. And he loved working with grad students, directing dissertations, shepherding the students through with his patient, gentle hand, offering wonderful advice on how to shape a project more effectively, and generously lending his prodigious skills as an editor. And it’s with the dissertations, as with his teaching, that the broadness of Chris’s interests made a big difference. He was equally willing to serve on a committee for a twentieth-century dissertation as for a nineteenth-century dissertation, or a Renaissance dissertation, or one delving into science fiction, or Latin American literature, or experimental fiction—because Chris loves all of these things. Time and again, Chris went where he was needed, including, more than once, taking over a committee just before it was about to implode. The word we keep coming back to is versatile. Every PhD student needing to take a language exam had to find someone in the Modern Languages Department to administer it—unless it was Spanish. Chris did those. In his remarkable capacity as what they call, in baseball, a utility player, Chris was downright Siebenschovian, and we’re really going to miss that.

I met Chris at my MLA job interview, where he asked me what I thought of Steven Soderbergh—because, I later learned, Chris doesn’t like Steven Soderbergh. I was effusively complimentary in my answer, and this was not the last time Chris and I would disagree about a filmmaker or a film. (I also note, for the record, that Chris likes John, and I like Paul.) Wherever MLA was that year, I remember riding down in the elevator with Chris literally one minute after the interview, and it was extremely awkward. I think we talked about the weather for what seemed like seventy floors. Thank God we didn’t talk about Steven Soderbergh.

It was not long after arriving at Case that Chris invited me to go see a movie, and then we went to another, and it became a regular thing, and a cherished part of my life these past twenty years. And sometimes the theater would be completely empty, and the film would be not very good, and we would start a loud, running commentary—and if the film was bad enough, Interstellar, for example, sometimes we would forget about the movie altogether. And I remember these conversations more fondly than any film we saw, especially Interstellar. I remember one time, the theater was empty, until about ten minutes in, when, unbeknownst to us, a little man in a wool cap sat down in the back row, and the movie was not very good, and our conversation was really starting to ramp up when we heard, from behind us, “Gentlemen!” And I’ll just say that some of my best memories of hanging out with Chris have that distinctly high school flavor, because it is fun to not act your age sometimes. But this story has a happy ending, for we got to chatting outside the Cedar Lee afterwards, and this man from Ireland turned out to have many interests, and Chris, ever reaching out and always friendly, promised, before we parted ways, to put this man on the Baker-Nord event e-mail list, as the English Department Colloquium Series had not yet begun.

But it wasn’t just about movies, and beer, although it was a lot about both. Once Jim Sheeler became an indispensable member of our league of extraordinary gentlemen, we did other things, along with, usually, something at a bar—and to give you an idea of how brave Jim was, he was adamant that we make it a karaoke bar some night. And, sadly, that plan was not realized, although maybe not so sadly for the other people who would have been there. And there was the Cleveland Indians game that Jim got us tickets for, and that was rained out. And we never did get to that makeup game. At a certain point, towards the end, we and the world migrated to Zoom, a brief time for us three that was more precious than any of us knew. Through bad times and good, Chris, you have been a good friend; and you have been a warm, stalwart, versatile, funny, irreplaceable friend to this department. Thank you.

Bidding Farewell to Mary Grimm

by Thrity Umrigar

The smile and the shrug.

The smile is ever-present, through good times and bad, lighting up that expressive face with the twinkling, mischievous eyes.

The c’est la vie shrug was deployed when the ridiculousness of the world—or, perhaps, merely the absurdities of the department—got too much. In the most challenging of times, including when Mary Grimm chaired the English department, her response to her responsibilities was never a groan or a frown. It was that shrug and that bemused smile.

But between the smile and shrug, lay a muscular, pedal-to-the-gas, shoulder-to-the- wheel work ethic. The complete, inexhaustible willingness to fall on the sword, to accept any assignment that would serve the interests of the department or the college. In other words, the casual demeanor hid a fierce commitment not just to her colleagues, but to the people we really serve—our students. Mary never lost sight of our true constituents. It was that knowledge that animated her every conversation, decision, and vote. It was what made her an essential force behind the decision to introduce a new Creative Writing Minor or a Creative Writing Practicum for our grad students. It was what made her volunteer to chair Writers House, a mere few years after she’d chaired the English department.

And her students sensed it. There are educators who have had buildings and libraries and halls named after them. But have you ever heard of a student being named after a professor? And yet, when Bruce Owen Grimm, who had been Mary’s student in the early 2000s, decided to change his name, he took Mary’s last name as his own. “If writers had ‘mothers’ like drag queens do, meaning someone who welcomes them into their ‘house,’ shows them care, support, and the wondrous things they are capable of, then Mary would be my writing ‘mother,’ Bruce said. “She was the first one to say to me, ‘You’re a writer.’ Anything I’ve ever been able to accomplish in my writing career is because she was the first one to believe in me and has been so supportive ever since. I wanted to pay tribute to her by taking her last name. I’m honored to be part of the House of Grimm. I hope I can live up to its legacy.”

I may not have taken Mary’s last name, but I do know that my entire career at Case is thanks to her. Here’s how it happened. But first, a joke:

Question: “What do they call a journalist with a PhD and a first novel?

Answer: “A journalist.”

And that indeed is what I was even after my first novel was published. But then Mary Grimm heard an interview I did on the local NPR station and invited me to do a book reading. It was my first time on Case’s gorgeous campus. I remember standing on the bottom step of Guilford and sending up a prayer to someday work in a place as lovely as that. But I immediately snuffed out that thought. Wishful thinking, I told myself.

The reading went well. I remember Mary smiling encouragingly throughout. It was as if she intuited that this was my first reading and that I was nervous. The student Q&A was great. I left there walking on clouds, but also strangely deflated. I felt as if I’d found my place and my people, but I had no path to join their ranks.

A few months later, Mary called me. She was going on a one-year sabbatical and they were interviewing people to fill her position. Would I care to apply?

Would I care to apply for a job in paradise? I thought. Um, yes, I think so. Even though the move meant leaving a secure and permanent job for a ten-month position. Even though I had no idea what the future would hold.

Over the years, Mary and I became more than colleagues—we became friends. Indeed, some of my most cherished memories of Case are of the time I’ve spent in Mary’s office shooting the breeze or of her walking into my office and plopping down on my couch to chat. In the early years, there was always a stash of dark chocolate in our offices, which we gleefully shared with one another. We would talk about books and writing and teaching, but I also leaned heavily on Mary’s counsel during the years I was taking care of my ailing father, because she’d gone through a similar journey with her mom. Indeed, the only really severe disagreement we’ve ever had was when I begged her to get rid of her beat-up office chair, yes, that infamous green chair whose bottom cushion had completely disintegrated. Mary reacted with horror and shock at the suggestion. She loved that chair and that’s all there was to it.

My love for Mary is only exceeded by my admiration for her. I remember emeritus professor Gary Stonum once saying that he believed Mary was the most well-read member of the department—quite the statement in a department filled with scholarly, brilliant people. Indeed, Mary is as voracious a reader as she is prolific a writer. Since 2019 alone, she has published a jaw-dropping number of short stories—over fifty by my count—while also working on longer works. And the quality of her writing is so unfailingly good. Her stories are populated with everyday events—going to the beach, visiting a dying parent, the bond between siblings. But something always lies curled in the center of the story and when you see it, it takes your breath away. That thing that lies curled only exists because, like all true artists, Mary knows how to look for the hidden things. Because Mary Grimm is the poet of everyday wonders, an observer of the human circus in all its absurdities and profundities. There is a wisdom and a wistfulness to her writing that affects me deeply. But don’t take my word for it. Take hers. These are a few lines from her short story, “Back Then,” published in The New Yorker in June 2019.

“Every year we bought treasures that we took home and set on our dressers to remind us of summer. All these things are gone now, and since I can’t believe that we’d ever have thrown them away, their disappearance has to have been caused by some process of time, some force that disintegrates and fragments fragile things when we’re not looking, when we forget to look.”

Mary, it is one of the joys of my life, that I never forgot to look. Because I always knew—and will always know—what a treasure we have in you. Thank you for everything. We will miss you terribly. You leave behind a gigantic legacy that we will cherish, but will never be able to duplicate.

A Tribute to Athena Vrettos

by Kurt Koenigsberger

When I met Athena in January of 2000, I was struck by her tremendous energy – on behalf of Victorian literature and of the English Department at CWRU alike. Her advocacy for the Department was all the more remarkable because she was just in her third year at the University, in the wake of a Guggenheim Fellowship term, with a young child on her hands, and so many other distractions as a relatively recent arrival to Cleveland. Nevertheless, she walked me around a frozen campus with almost a conspiratorial enthusiasm for the future of English at Case and its graduate program in particular. At a now-defunct restaurant in Little Italy, we found ourselves quoting from Gaskell’s Cranford in unison – at which point I knew I wanted to be part of such a warm and welcoming community, shot through with such enthusiasm.

Athena’s energy is always infectious and compelling. In a breakfast with Bill Siebenschuh on the occasion of the same visit, he put me on notice that the future of the Department belonged to Athena and Chris Flint. Speaking institutionally, for the past quarter century, Athena and Chris have centered the department’s gravity – and in many ways shouldered its many burdens. Speaking personally, I think it’s fair to say that Athena drew me to Case Western Reserve in the first place by the force of her affection and enthusiasm for the Department. Once here, one of the burdens Chris shouldered was mentoring me; he guided me in ways that have let me and my family grow in Cleveland and at CWRU.

Athena’s energy has always been fired in the first place by the classroom environment, from which her undergraduates emerge positively vibrating after the heat and light of discussion – about children’s literature (Semester I or Semester II, no matter!), about medical narrative (for SAGES students), or about Victorian literature and the body (for advanced undergrads). It is no surprise – and our undergraduate students would be the first to find it unsurprising! – that she was nominated for and won the College’s Undergraduate Teaching Excellence Award. It’s perhaps worth noting that Athena also consistently disappointed graduate students with respect to those children’s lit classes, restricting them to undergraduates, where she could work in innovative ways that the demands of a graduate curriculum don’t necessarily permit.

But in any event our graduate students cannot be too disappointed, because they have drawn more than their share of inspiration from Athena’s Victorian Lit and Psychology grad seminars – a veritable feast laid out expertly in relation to her own deep scholarship into phenomena of embodiment, mind, and their strange entanglements in nineteenth-century scientific and imaginative formulations. Her 1995 book Somatic Fictions, as well as her many essays, reviews (as, for instance, of Nicholas Dames’s Amnesiac Selves), and personal connections (Joseph Valente, e.g.) provided rich and fertile ground on which several generations of Master’s and doctoral students were able to cultivate their own research projects and make their scholarly homes.

Among those whose research and writing – indeed, careers! – were fundamentally shaped by Athena’s teaching, I count Drs Kelly, Kichner, Kungl, Ryan, Mitchell, Schillace, Fejes, McDaniel, Nielson, Kondrlik, and Banghart – with another, Davydov, on the near horizon. Having served on many of these committees alongside Athena, I can attest to her approximation of the role of the ideal reader envisioned by Henry James in his Notebooks, and which she quotes approvingly in a chapter of Somatic Fictions: she is “admiring, inquisitive, sympathetic, mystified, skeptical.” Athena was honored for her deeply distinguished and insistently inspiring graduate instruction with a John S. Diekhoff Teaching Award. As far as I know, only one other faculty member in the past half-century has been comparably honored both for undergraduate and graduate teaching (the late P. K. Saha) by the College and University.

Professor Siebenschuh’s conviction at the close of the last century that the English Department in the new century would owe so much to Athena’s professional and programmatic vision has proved prescient indeed. My many early conversations with Athena – both before my official arrival in Cleveland, and in my first years at CWRU – had to do with modernizing the department’s graduate program and rendering it a richer and more humane experience. At the time, the program asked a tremendous amount of ABD doctoral students in particular, effectively demanding that they teach a full-time load (that is, full-time for tenured faculty!) in exchange for a pittance (I think the figure might have been $7000 in 1999 for four courses per year). We also had a significant number of full-pay master’s students who were working full-time, studying full-time, and taking out loans to make it all work. Athena worked tirelessly to raise stipends and working conditions for students so that the Department could really envision a resident community of graduate scholars. The levels of engagement we see from current graduate student cohorts would simply be impossible without the material ways in which Athena advocated for the program over a full decade.

In her two substantial terms as Grad Director (1999-2003 and 2005-08; she also served another term as Interim Director in the late ‘teens), Athena provided a roadmap for bringing all grad students along a path to professional development, whether preparing them for the academic job market or giving them opportunities in relation to Department visitors and searches. The Department found that it could advertise a consistent and rewarding experience to all graduate students for the first time, and students could count on Athena personally as their DGS to guarantee this consistency and quality. She ensured this roadmap would be followed even beyond her tenure as DGS, because in between her two terms she mentored Todd Oakley when he was DGS, and her playbook guided Chris Flint as he followed her into the next decade as DGS.

For a scholar and a teacher with such a frequently expressed antipathy toward administration, Athena certainly had a curious knack for it. After leaving the grad program in the capable hands of Professor Flint, Athena increasingly turned her attention to the undergraduate experience – working for most of the past decade on the Department’s Undergraduate Committee and even serving as Interim Director of Undergraduate Studies for a period. In that context, her classroom energy, rigor, and high expectations gave definitive shape to our undergraduate curriculum, including – to note only a very recent instance – working to codify the expectations for our research-intensive Departmental Seminars, required of all English majors.

Fittingly for a scholar of Henry James, Athena has inhabited essential ambassadorial roles for English. In many ways, she (and Chris!) have become heirs to the generosity, hospitality, and commitment to community that the late Roger and Betty Salomon exemplified for so many decades. I suspect it has been the experience of just about every new colleague since 2000 that Athena has performed some essential outreach work on behalf of the department, drawing us all into the fold in ways that make us seem not just welcome but deeply needed by our small community. In my own case, this work involved long phone calls with me – both prior to, and following, my acceptance of CWRU’s offer – as well as a long afternoon on Chalfant Road in Shaker when Athena and Chris opened their home to me and Kristin during our first visit to Cleveland.

Still more, Athena has made herself available as a mentor, both formal and informal, for other faculty – not just in English, but also in Women and Gender Studies and across the medical humanities at CWRU. And, if such an application of the term be admitted, she and Chris have mentored the department as a whole, either hosting or arranging for the hosting of scores of departmental functions that have helped to bind our community together. As one final index of the commitment simultaneously to the study of Victorian literature and culture, its teaching, and the communities it can organize – Athena also regularly invited her graduate seminars to her home for Victorian High Tea, a memorable feature of her 500-level courses that many students remember fondly. It is with a particularly keen regret that I discover at the end of her teaching career (though not her writing career, as she still has several articles yet to appear on Victorian psychology and affect) that because I could never be a student in her graduate seminar, so I was never in a position to be invited to such an afternoon. On the occasion of her retirement, I find myself nostalgic for a tea I must always have missed, in a perverse formula that Professor Vrettos no doubt would take great delight in unpacking in her scholarly writing and in her seminar room alike.

Department News

Barbara Burgess-Van Aken is offering a Shakespeare class this June through Siegal Lifelong Learning.

Gabrielle MW Bychowski presented a Plenary session at the Sewanee Medieval Colloquium at the University of the South.

Michael Clune gave the lecture “Hugh Kenner’s Modernism” at Princeton University on April 7.

Thom Dawkins was featured by the College of Arts and Sciences for National Poetry Month.

Charlie Ericson is the recipient of the Timothy Calhoun Memorial Prize for Poetry for the best poem or group of poems by a graduate student in the Department of English.

Narcisz Fejes received the The SAGES Excellence in Writing Instruction Award.

Mary Grimm had a flash piece in Whale Road Review.

Dave Lucas received the 2022 Carl F. Wittke Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching.

Michelle Lyons-McFarland is presenting in a workshop “Tilting at Windmills: A Descriptive Bibliography of Charlotte Lennox” at the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies annual conference for 2022.

English major Veronica Madell has been awarded a Fulbright U.S. Student Program Grant.

Through a Freedman Fellowship, Francesca Mancino created a Scalar site focusing on the life and work of Hart Crane in hopes of converging his scattered institutional archives.

William Marling discussed his book, Christian Anarchist: Ammon Hennacy, A Life on the Catholic Left, on Roger McDonough’s podcast on KCPW (NPR) in Salt Lake City.

Marilyn Mobley‘s review of William James Jennings’s After Whiteness: An Education in Belonging will appear in the Wesleyan Theological Journal.

James Newlin‘s chapter “Søren Kierkegaard’s Adaptation of King Lear” appears in the new Bloomsbury volume Disseminating Shakespeare in the Nordic Countries: Shifting Centres and Peripheries in the Nineteenth Century, edited by Nely Keinänen, and Per Sivefors.

Steve Pinkerton has an essay on “Harlem’s Bible Stories: Christianity and the New Negro Movement” coming out in The Edinburgh Companion to Modernism, Myth, and Religion (slated for January).

Camila Ring is the recipient of the Graduate Dean’s Instructional Excellence Award from the School of Graduate Studies.

Meredith Steck received The WRC Excellence in Consulting Award.

Thrity Umrigar discusses her new novel Honor on Ideastream.

Maggie Vinter‘s book chapter “Othello’s Speaking Corpses and the Performance of Memento Mori” was published in The Shakespearean Death Arts, ed. William Engel and Grant Williams (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022).

The final two articles in Athena Vrettos’s series on Victorian literature and psychology will be coming out later this year. The first is titled “Wandering Attention: Victorian Daydreaming, Disembodiment, and the Boundaries of Consciousness.” It’s in an edited collection titled Life, Death and Consciousness in the Long Nineteenth Century, edited by Michelle O’Connell and Lucy Cogan, in Palgrave-Macmillan’s Literature, Medicine and Science series. The second is titled: “The Temporality of Emotional Traces in Victorian Fiction and Psychology,” and is forthcoming in a collection titled Connecting the Dots: Conceptualizing ‘Trace’ in the Nexus of Novels and Readers’ Sensory Imaginings, edited by Monika Class.

Constance Fenimore Woolson’s Revival

by Hayley Verdi

On April 8th, 2022, Anne Boyd Rioux, associate professor at the University of New Orleans, visited CWRU to give the annual Sadar Lecture. Her lecture, “Constance Fenimore Woolson: The Story of Her Revival and Why the Recovery of 19th-Century Women Writers Matters,” coincided with the 14th Biennial Conference of the Constance Fenimore Woolson Society held in Guilford House on April 8th and 9th.

If one lesson can be drawn from Rioux’s lecture, it is the transformational power of knowing and caring for the needs of an audience. This year’s Sadar Lecture was well attended, hosting both members of the English Department and the wider CWRU community as well as members of the Constance Fenimore Woolson Society. As a result, Rioux spoke to an audience composed of both the leading experts on Woolson as well as a number of audience members, myself included, who were just being introduced to Woolson and her work. Under the expert guidance of Rioux, audience members of all levels of knowledge found themselves led toward both an understanding of Woolson’s contributions to literary history as well as the pressing need for high quality and accessible humanities scholarship.

Equal parts rigorous research and practical advice, this talk provided listeners with a strong argument for the need to move our research beyond the boundaries of academic institutions to a wider readership. Roux drew a direct line from her academic research on the works and life of Constance Fenimore Woolson to her passion for coaching and mentoring young writers. By expanding her reader’s knowledge of our “literary ancestral tree,” Rioux argued that these kinds of literary revivals can help to support women writers today. Once one of the most popular and well regarded writers of the 19th Century, Constance Fenimore Woolson was largely forgotten until the efforts of scholars such as Rioux to revive her work. As Rioux observed, Woolson is an example of a writer whose invisibility is not only lamentable but harmful. She explained, “The invisibility of yesterday’s women writers contributes to the disregard of women writers today.” In working to revive the reputations and work of women writers of the past, Rioux convincingly demonstrated that humanities research has the potential to benefit both the members of academic communities as well as the general public.

Not only was the structure of Rioux’s lecture a masterful model for how to present research on a little known topic, it was also a call to all researchers in attendance to (re)consider the needs of their audiences. After providing a thorough overview of Woolson’s literary career and highlighting how Woolson has continued to rise in popularity since the founding of the Woolson Society, the publication of Rioux’s biography of Woolson, and the release of Rioux’s edited complete collection of Woolson’s stories by the Library of America, Anne Boyd Rioux directly challenged us all to consider who we write for and how that might shape our approach to our work. Rioux pointed to both her decision to work with a trade publisher to release her biography on Woolson as well as to her choice to publish pieces on Woolson and other forgotten women writers in popular magazines and websites as two examples of how researchers might engage a wider, more varied audience. As Rioux explained, there are audiences eager for the kinds of research and writing humanities scholars produce; more often than not, however, they are to be found outside the lecture halls and libraries of university campuses.

Writing Faculty & Student Awards Announced

The Writing Program Awards Ceremony recognizes and celebrates the accomplishments of student writers and writing faculty at CWRU. Writing is fundamental to the work of the university: our words enable the development and circulation of knowledge, create and sustain our communities, and advocate for social and community action. Congratulations to the writing faculty whose expertise and dedication have supported our writers at all stages of their careers. Congratulations, also, to the student essayists whose work is celebrated this year.

The Jessica Melton Perry Award for Distinguished Teaching in Disciplinary & Professional Writing recognizes outstanding instruction in writing in professional fields and/or disciplines other than English.

This year’s winner is Dr. Jennifer Carter, Associate Professor of Materials Science and Engineering. As described by one of her students in their nomination, Dr. Carter creates a “positive cowriting space” in her team meetings. In Dr. Carter’s research group, students learn to read collaboratively as well as to offer valuable feedback to their peers (and themselves) on their writing projects. Thus, Dr. Carter not only values but fosters the practice that is at the heart of all academic publishing: peer-review. In her own remarks at the Awards Ceremony, Dr. Carter emphasized the value of being vulnerable herself as a writer in her work with students, sharing her own writing experiences and challenges as she models ways to address and overcome them.

The SAGES Excellence in Writing Instruction Award recognizes outstanding commitment to and success in teaching academic writing to CWRU undergraduates in SAGES.

This year’s winner is Narcisz Fejes, Lecturer in English and SAGES Teaching Fellow. Nominated by several students, Dr. Fejes is recognized throughout the university for her patience, kindness, and generosity as a writing instructor and mentor.

One of her nomination letters described how Dr. Fejes worked with a student across all of their time at CWRU:

“When I was an undergrad student, I took one SAGES class with her. She designed various class activities such as reading, visiting farmer markets, watching documentaries, etc, to help students better understand the overall topic, Food, of the class. After finishing the class, I have attended a lot of her writing resource center sessions, and we worked on my capstone, publication manuscript, and graduate school application materials (personal statement, diversity letter). I am currently admitted to a few schools, and I feel Dr. Fejes definitely played an important part here. She helped me not only on one article or assignment, but she provided me ideas and some general guidelines on how to work on other similar articles or assignments.”

The WRC Excellence in Consulting Award recognizes outstanding writing instruction for students of the University and exemplary service to the Writing Resource Center during the academic year. This year, two consultants stood out both in their quantity of nominations as well as in the high quality of the consulting work their nominators described: Bernie Jim, Lecturer in History and SAGES Teaching Fellow, and Meredith Steck, Lecturer in English and SAGES Teaching Fellow.

One of Dr. Jim’s consultees described him as “absolutely amazing! He helps you understand where you can improve. All of my sessions with him have been productive and I have never felt ashamed to show him my writing. He gives clear suggestions and helps you to bounce ideas off of him.” As a SAGES Teaching Fellow and WRC Consultant, Dr. Jim has long been recognized for giving helpful feedback, being open to learning from his students, and always being willing to help in any way.

Similarly, Dr. Steck’s nominations included this glowing praise:“Top reasons why Meredith should be recognized with the Excellence in Consulting Award:

(1) Meredith meets students where they are in their writing journey and writing process. Motivation, tough feedback, and grammar refinement are not unique in themselves, but Meredith uses these tools and techniques at the perfect moments to ensure that students always feel supported, encouraged, and successful.

(2) Meredith assists students in branching out from the standard essay writing to fellowships, PowerPoint presentations, etc. She also goes above and beyond to help students connect with individuals in other writing realms (e.g., Spanish writing).

(3) Meredith highlights her students’ strengths while providing constructive feedback to enhance their weaknesses. I have recommended her to many undergraduate students, graduate students, and faculty at CWRU.

(4) Meredith is EXTRAORDINARILY welcoming making sessions joyful and fun. I have been meeting with Meredith 1-2 times a week for the past two semesters; I leave each session as a stronger writer and better person.”

The English Department’s graduate students make a significant contribution to the Writing Program each semester as writers, teachers, and Writing Resource Center consultants.

This year we recognize two graduate students for their excellence in creative writing and instructional excellence.

PhD student, Charlie Ericson, is the recipient of the Timothy Calhoun Memorial Prize for Poetry, for the best poem or group of poems by a graduate student in the Department of English. Camila Ring, is the recipient of the Graduate Dean’s Instructional Excellence Award from the School of Graduate Studies.

The SAGES First and University Seminar Essay Prizes recognize the best writing that students produce in their First and University Seminars. These essays are chosen from those nominated by SAGES seminar leaders each semester. The following students were awarded essay prizes for their writing in seminars led between Fall 2020 and Fall 2021.

You can read their essays on the Writing Program Website Writing Awards Page.

University Seminar Essay Prizes (2020-2021)

Blake Botto for “Proposal for Change: Building a Bridge to a New, More Diverse Audience for Cuyahoga Valley National Park,” written for USNA 265: Thinking National Parks (Seminar Leader: Eric Chilton)

Claire Hahn for “Redistributing Power through Magical Realism: Pan’s Labyrinth and The Shape of Water,” written for USSY 293G: Magical Realism in Fiction and Film (Seminar Leader: Joshua Hoeynck)

Sofia Lemberg for “The Use of Music as a Tool of Queer Allyship by Non-Queer Artists,” written for USSY 294D: 20th Century American Music and Cultural Criticism (Seminar Leader: Andrew Kluth)

Mirra Rasmussen for “Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Consistency and Inconsistency in the Face of Transgender Identity,” written for USSO 291Y: Immigration, Identity, and Writing (Seminar Leader: Luke Reader)

University Seminar Essay Prizes (2021-2022)

William Dehmler for “Purifying the Toxic Substances Control Act,” written for USNA 287: Society & Natural Resources (Seminar Leader: Scott Hardy)

Jackson Jacobs for “Two Decades in Afghanistan on American Feminism,” written for USNA 289X: Sexual Revolutions (Seminar Leader: Einav Rabinovitch-Fox)

First Seminar Essay Prizes (Fall 2021)

Adam Rohrer for “Letter to Governor DeWine,” written for FSSO 185A: Adulting (Seminar Leader: Karie Feldman)

Ethan Teel for “Facing Existential Fears in Children’s Metafiction,” written for FSSY 185R: Children’s Picture Books (Seminar Leader: Cara Byrne)

Cordelia Teeters for “Over My Dead Body,” written for FSSO 185: Caskets & Corpses: The American Funeral Industry (Seminar Leader: Vicki Daniel)

Alumni News

Erin Clair (’99), Professor of English at Arkansas Tech University, has been appointed as Associate Dean in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Andi Cumbo-Floyd (’01) writes under the name ACF Bookens. Here she is being interviewed on PBS about her mystery series.

Iris Dunkle (‘10) has 3 poems in The Bombay Literary Magazine.

Jeff Morgan (‘99) has two poems in the latest edition of Grist.

Brad Ricca (’03) writes about the first school shooting in the Washington Post.

Brandy Schillace (’10) is a finalist for the Ohioana Book Award in Nonfiction.

Alum (‘10) Marie Vibbert’s novel The Gods Awoke will be published this fall by Journey Press.

Graduation 2022

Pictured (l to r): Kurt Koenigsberger, Kim Emmons, Micah Stewart-Wilcox, Madeleine Gervason, and Brita Thielen. Not pictured, MA grad Francesca Mancino.

Send Us Your News

If you have news you would like to share in a future newsletter, please send it to managing editor Susan Grimm (sxd290@case.edu). If you wish to be added to our mailing list, just let us know.

The department also has a Facebook page on which more than five hundred of your classmates and profs are already sharing their news. Become a member of the community and post your own news. We want to know. The department will be posting here regularly too—news of colloquiums, readings, etc. Also, we tweet @CWRUEnglish.