Stonum Visiting Writer/USEM Prizes/Department News/Constance Fenimore Woolson/Alumni News/Poem by Saha

Tom Bishop Returns as First Stonum Family Fund Writer-in-Residence

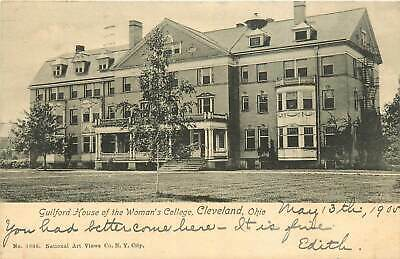

Tom Bishop, Marilyn Stonum, Gary Stonum on the stairs of Guilford House.

by Charlie Ericson

Tom Bishop was a visitor at CWRU for a week-long residency in February, sponsored by the generous gift of the Stonum Family Fund. Bishop was a member of the English Department for eighteen years, leaving in 2006 to take up a post at the University of Auckland.

“First, translation is inevitable.” This was one of several tenets of translation set out at Tom Bishop’s February 18th colloquium. This sounds pessimistic—like we will never, even when looking at a source text, have access to it except through our personal translations into our own understanding. But another of Bishop’s tenets turns this on its head. “Translation,” he says a few minutes later, “is a kind of apocalyptic opening up.” He cites Walter Benjamin here, and suggests that when we engage with the act of translation we are at our closest to what is sacred in a text. Throughout Bishop’s week-long residency as the inaugural Stonum Family Writer-in-Residence, this dual sense was at play. His colloquium talk positioned the high literary texts of Gautier, Verlaine, Hesse, and Goethe alongside pop tunes and dance music, emphasizing most of all the jigsaw-like joy of pulling at the threads of language. It’s necessary, for Bishop, that you still are able to sing the translated poem along with the original version. In his translation masterclass, he asked each student what compelled them to work on that text, to live in that voice, and where in their body they could feel the poem working on them. Ovid’s voice, in his example, was “naughty”—and it held him by the gut.

Any reader of Bishop’s scholarly work (his well regarded Shakespeare and the Theatre of Wonder, for example, written in his time at CWRU) recognizes his rigorous historical research and attention to argument. But when he sits down to translate, he’s always rethinking his priorities. Do we need the meter to sing along? Or is this phrase just too important to lose? When you translate the word torrero, does “bullfighter” carry the same weight in English? Or should that be, as Bishop suggested, “rockstar”? Bishop didn’t dismiss literal academic translation—far from it. He was more interested, though, in producing translations that communicate the effect of a poem to an English-speaking audience, rather than the literal sense of each word. If translation is inevitable, as Bishop suggests, then why not try to bring your reader that sacred thing, that fist in your gut? They won’t have the language, but Bishop might say they’ll get something greater.

SAGES University Seminar Essay Prize Winners Announced

Awarded annually, the SAGES University Seminar Essay Prizes highlight the best student writing produced in SAGES University Seminars each year. SAGES and the Writing Program are delighted to announce that the following four writers have been selected from among more than forty nominations across more than one hundred seminars to receive the prize for 2020-2021.

Proposal for Change: Building a Bridge to a New, More Diverse Audience for Cuyahoga Valley National Park

by Blake Botto

Written for USNA 265: Thinking National Parks (Seminar Leader: Eric Chilton)

Redistributing Power through Magical Realism: Pan’s Labyrinth and The Shape of Water

by Claire Hahn

Written for USSY 293G: Magical Realism in Fiction and Film

(Seminar Leader: Joshua Hoeynck)

The Use of Music as a Tool of Queer Allyship by Non-Queer Artists

by Sofia Lemberg

Written for USSY 294D: 20th Century American Music and Cultural Criticism (Seminar Leader: Andrew Kluth)

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Consistency and Inconsistency in the Face of Transgender Identity

by Mirra Rasmussen

Written for USSO 291Y: Immigration, Identity, and Writing (Seminar Leader: Luke Reader)

Recipients of the prize receive a cash award and recognition at the annual Writing Program Award Ceremony at the end of each academic year. The authors also work with the Writing Program to edit and publish their projects on the Writing@CWRU website.

You can read their prize-winning research projects here.

Congratulations to the winners and their seminar leaders!

Department News

Cara Byrne gave the lecture “C is for Coronavirus, P is for Pandemic: Covid-19 in Children’s Picture Books” at the Baker-Nord Center for the Humanities in March.

Barbara Burgess-Van Aken offered the course “More of Will’s Willful Women” through Siegal Lifelong Learning.

Michael Clune‘s piece on dreams is the cover story of this month’s Harper’s.

English major Jo Goykhberg is featured in The Daily.

Mary Grimm‘s story “Boundary Object” was nominated for Best Small Fictions by the South Florida Poetry Journal.

Francesca Mancino interviewed Dr. William Maxwell on the Harlem Renaissance for Five Books.

New York University Press has published the seventh scholarly book of William Marling. The book, titled Christian Anarchist: Ammon Hennacy, A Life on the Catholic Left, illuminates an “exemplar of vegetarianism, ecology, and pacifism.” James Fisher, editor of The Catholic Studies Reader, noted that it is “an important contribution to the literature of 20th century American radicalism.”

Marilyn Mobley was interviewed about Toni Morrison on the “Seneca 100 Women to Hear” Podcast.

John Orlock is a recipient of an Ohio Arts Council 2022 Individual Excellence Award in Playwriting.

Anthony Raffin will be presenting on Don DeLillo’s White Noise at the American Literature Association’s annual conference in May.

Brita Thielen‘s article, ““Ethos, Hospitality, and the Pursuit of Rhetorical Healing: How Three Decolonial Cookbooks Reconstitute Cultural Identity through Ancestral Foodways,” was recently accepted by Rhetoric Review. This article is adapted from Brita’s dissertation, and an earlier version of the paper was awarded the 2019 Neil MacIntyre Memorial Prize by the CWRU English Department.

Thrity Umrigar‘s new book, Honor, is a Reese’s Book Club title. Thrity was featured in a recent issue of artsci.

Anthony Wexler offered the course “Primo Levi’s Legacy” through Siegal Lifelong Learning.

Constance Fenimore Woolson—and the Ghosts of Guilford House

by Dennis Dooley

The ghosts of several important figures from Cleveland’s (and CWRU’s) past may be hovering about Guilford House on Friday, April 8th, when Anne Boyd Rioux presents the Sadar Lecture on a long-forgotten Cleveland author who’s been getting more and more attention in the last few years. Maybe even the ghost of Henry James.

Have I captured your curiosity?

Constance Fenimore Woolson (1840–1894) was the grandniece of James Fenimore Cooper. But that, in the course of time, would prove the least of her claims to fame.

Woolson was a schoolgirl of fourteen when Linda Thayer Guilford came into her life. It was 1854 and Guilford was de facto principal of the Cleveland Female Seminary and its most prominent female teacher. (In those days, seminary was just another word for academy and carried no religious connotations, though the girls lucky enough to attend that forward-looking school near E. 55th and Kinsman were encouraged to read, think about serious things and, albeit within the social constraints of the time, make something of their lives.) Linda Guilford was a graduate of Mt. Holyoke College, a pioneering institution in the still young movement to make serious higher education available to women, who were restricted to learning the decorative arts and social skills offered by finishing schools.

Under Guilford, teenage girls received the equivalent of a college-prep education in Latin, philosophy, English literature, and the history of England and America, as well as chemistry, physiology, zoology, algebra, and trigonometry. And so, writes Anne Rioux, while “outside the snow blew sideways through the wide-open fields . . . Constance bent over her desk each week to write her compositions. And each week Miss Guilford patiently corrected her errors in logic and pointed out her faults in style. She was the budding writer’s first critic, setting a high mark Constance was anxious to reach.” So, after Woolson began, in her twenties, to have her stories accepted by the likes of William Dean Howells and published in magazines such as Harpers, Lippincott’s, and The Atlantic Monthly, she kept a special place in her heart for Linda Guilford.

But file that away for now.

The recognition of her talent she was now receiving (which included a $1,000 literary prize) vindicated Woolson’s rejection of her mother’s advice that she marry a nice gentleman with money and prospects like the man her sister Georgiana had wed at nineteen, one Sam Mather. Alas, poor Georgiana died of tuberculosis just three years into that marriage—but not before she’d been delivered of a bouncing baby boy they christened Samuel Livingston Mather, who would grow up to become one of Cleveland’s most successful industrialists and philanthropists.

When in 1879, Woolson, by then a restless world traveler and confirmed ex-pat, returned from England to help tend to her dying mother, her nephew Sam introduced her to his fiancée, twenty-seven-year-old Flora Stone, the youngest daughter of Amasa Stone, a fabulously successful builder of railroad bridges. Stone had been a deeply troubled man ever since the catastrophic collapse in 1876 of his bridge over the Ashtabula River that had taken ninety-two lives, making it the worst railroad accident of the nineteenth century. An investigation concluded that the bridge had been badly designed, poorly constructed, and inadequately inspected. In an attempt (it was whispered) to restore his good name, in 1882 Stone underwrote the cost of moving Western Reserve Academy (founded in 1826) from Hudson to Cleveland to form the basis of a badly needed university. A year later, the deeply depressed Stone ended his own life, and young Flora came into a staggering fortune, with which she determined to do as much good as possible in the world.

Her greatest project was establishing, on the new university’s campus, a college for women that would one day be given her name in gratitude. Flora was responsible for five buildings that stand to this day: Harkness Memorial Chapel, Clark Hall, Haydn Hall, the Mather Memorial Building on the corner of Ford and Bellflower, and, in 1892, what was originally called Guilford Cottage, a dormitory for young women who hungered for more. It seems the same determined young educator who had been such an important mentor to Constance Woolson had done the same for Flora Stone and her sister Clara. (Guilford’s papers are now preserved at CWRU. Her books, The Story of a Cleveland School from 1848 to 1881, The Use of a Life, and Margaret’s Plighted Troth are available through your favorite bookstore.)

It was Clara’s husband, John Hay, the late President Lincoln’s private secretary and shortly to become the (anonymous) author of the first novel ever set in Cleveland, who introduced Woolson to his good friend Henry James. James and Woolson would become close friends, taking long walks and spending delicious evenings together in conversation. Their relationship is explored at length in Colm Toibin’s 2004 novel The Master. Indeed, says Rioux, there is ample evidence to suggest that Woolson was part of the inspiration for the protagonist of The Portrait of a Lady, the first draft of which James was writing when they met in Florence. “[He] saw in his new friend no small portion of the spirit he was trying to capture on the page,” Rioux believes. “No wonder he took time off from his work to show her around the museums and churches of Florence for four weeks.” When she read the published novel, Woolson told James she felt “a perfect sympathy, & comprehension, & a complete acquaintance” with its protagonist. After all, says Anne Rioux, “She knew Isabel as well as she knew herself. Like her, Woolson did not conform to most men’s idea of an agreeable woman. She was too self-contained, in the terminology of the day. Neither possessed the uncomplicated, undiscriminating nature prized in women.” Women like Isabel (and, by implication, herself), Woolson explains, are “idealizing” and “imaginative”; and thus, the novelist in her is compelled to add, with the insight and candor that no doubt first attracted James to her, “sure to be unhappy.”

When, two years later, word reached him that Woolson had died in Rome, in a fall from a third story window, he visited her grave, and spent two weeks helping clean out her apartments, often pausing to read her notebooks. Perhaps recalling Woolson’s conviction that “houses in which persons have lived, become after a time, permeated with their thoughts,” he rented the rooms she had occupied in Oxford. Out of this came his story, “The Altar of the Dead.” In the years that followed, says Rioux, “James would write many more works that scholars have suspected were inspired at least in part by his complicated friendship with Woolson. “The most fully realized is ‘The Beast in the Jungle,’ published nine years after her death,” which grew, Rioux says, “from an idea in Woolson’s notebooks: ‘To imagine a man spending his life looking for and waiting for his “splendid moment.” . . . But the moment never comes.’”

Constance Fenimore Woolson’s moment, on the other hand, seems to have come at last. Reviewing “Miss Grief” and Other Stories, Rioux’s 2016 selection of Constance Fenimore Woolson’s short fiction, The Wall Street Journal said she had “paved the way for authors such as Edith Wharton, E. M. Forster, and Willa Cather”; The New York Times, that Woolson’s stories “demonstrate irony, force and feeling that occasionally surpass the stories of Edith Wharton and Howells, rivaling ‘the Master’ [Henry James] himself.” James said equally glowing things about her novels in an 1887 article he wrote for Harper’s Weekly.

This year Woolson is being celebrated as one of Cleveland’s Past Masters (https://www.pastmastersproject.org/ ).

In her lecture on April 8th (Clark Hall 206, 3:15–4:15), Anne Boyd Rioux tells the story of Woolson’s revival and reflects on the importance of recovering nineteenth-century women writers. On Thursday, the Cleveland History Center offers a tour of the Hay-McKinney Mansion; and on Friday and Saturday, Guilford House will be the site of the Constance Fenimore Woolson Society’s 14th Biennial Conference.

Dennis Dooley, a former faculty member of the English Department, conceived, and is coordinating, the year-long, citywide celebration of Cleveland Past Masters co-sponsored by Cleveland Arts Prize and the Western Reserve Historical Society.

Alumni News

Kent Cartwright (’79) has just published a new book, Shakespeare and the Comedy of Enchantment (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Shelley Costa (’83) (writing as Stephanie Cole) has a new book out: Evil Under the Tuscan Sun.

Iris Dunkle (’10) has two poems in Third Wednesday.

Sarah Forner (’18) has accepted a position as Director, Corporate Relations with The University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana.

Terri A. Mester (’93) is offering a class, “More Cinema of Otherness,” through Siegal Lifelong Learning.

Aparna Paul (’21) is a spring intern at Literary Cleveland.

Alum (’03) Brad Ricca‘s graphic novel comes out in April: Ten Days in a Madhouse.

Brandy Schillace (’10) is the recipient of an Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award for Non-fiction.

Carrie Shanafelt (’03) gave a talk on Jeremy Bentham on the “Pleasures of the Bed” in January.

Nadia Tarnawsky (’96) will be leading a workshop in Ukrainian folk songs. Proceeds will benefit humanitarian aid in Ukraine.

Marie Vibbert (’98) is on the British Science Fiction Awards long list for best novel and best short story.

What Lies Below the Tracks

by P.K. Saha

Early in childhood, I lost count of how many times

my family went back and forth

on the 900-mile train journey between Delhi and Calcutta.

Often I fell into a trance as I gazed

at parallel tracks endlessly separating and merging.

Delhi followed Calcutta as Capital of British India,

and the stations between them were fixed in my memory:

Mughalsarai, Aligarh, Benares, Allahabad, Patna…

The British planners did not locate the stations by accident.

Three centuries earlier Emperor Akbar, a contemporary of Queen Elizabeth,

built a caravanserai route for merchants

who carried goods east from Delhi and elsewhere.

All those stations built by the British are located on sites

where serais or inns stood in Akbar’s time.

To this day I can lull myself to sleep on troubled nights

by recalling the drowsy cries of vendors on the platforms:

paan… biri… sigret…

paan was betel leaf stuffed with spices and nuts,

biri was a native cigarette,

and sigret meant English cigarettes.

History reaches deeper in India. Two and a half thousand years ago,

the Buddha walked back and forth preaching

where the city of Patna was later located by the British.

In the 1940s it took a day and a half

for the train to go from Delhi to Calcutta.

In a new century now, any drowsy moment

can set me rolling on the tracks again.

I gaze at tracks of history merging and separating

and wonder if more buried secrets might emerge

before I myself am part of the past.

July 2021 P.K.

Send Us Your News

If you have news you would like to share in a future newsletter, please send it to managing editor Susan Grimm (sxd290@case.edu).

The department also has a Facebook page on which more than five hundred of your classmates and profs are already sharing their news. Become a member of the community and post your own news. We want to know. The department will be posting here regularly too—news of colloquiums, readings, etc.